I am expecting to get to the age of Caravaggio’s St Jerome and still be trying to work out how to put into words what I’m trying to express in paint. Like Edward Hopper, I think the ‘statement’ is hanging right there on the wall and having spent countless hours trying to produce the effect I’ve been aiming at, it does seem somehow perverse to try to render it in another medium. The fact is, there are fundamental regions of our senses and responses where visual art operates that defy rational explanation but nonetheless enrich us and increase our understanding of what we are, even if we can’t quite make the translation for the sake of our conscious minds.

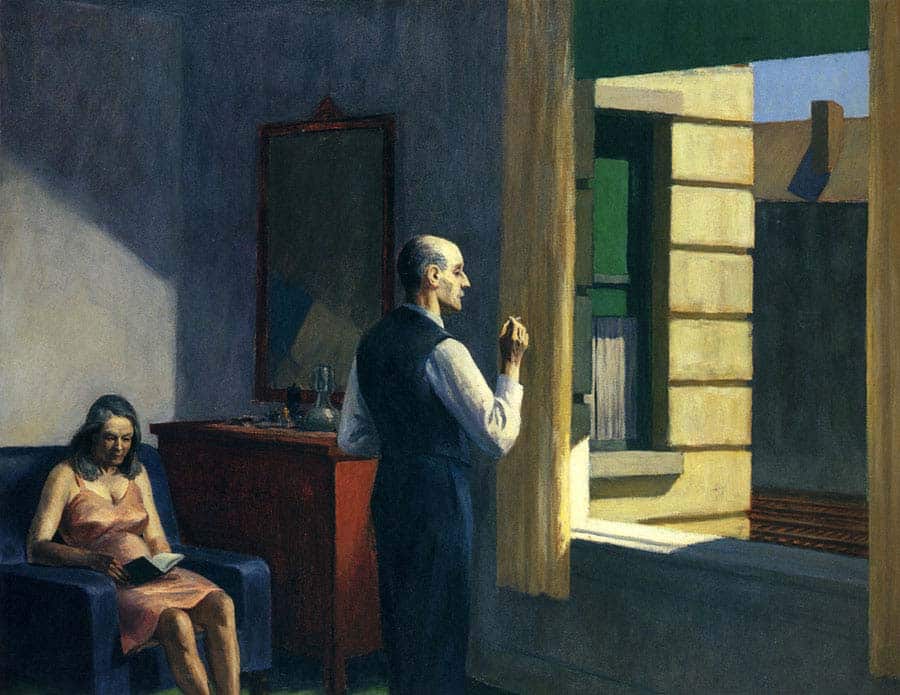

Hopper is very much a case in point. His paintings are loaded with narrative content that invites commentary but that is only the beginning. The colours, composition, the expressions and dispositions of the characters and the use of light moves us in a way that calls on something much more deep-seated and indefinable, as if the paintings are stirring experiences buried within our subconscious.

Maybe this is a bit old fashioned and, given the immense diversity we have in ways of seeing and creating artworks, words are now just another element in the landscape, but, for myself, there is always something going on in a painting that eludes any attempt to rationalise the experience, either of viewing or of creating the work.

Having said this much, I have to admit that writing about art is a very compelling business. Even the taciturn Hopper allowed himself the occasional insight and he was obviously a very deep thinking and contemplative man. I like the comment from his wife, Jo, that went something like, ‘Having a conversation with Eddie can be like dropping a stone into a well. Only you don’t hear the thud when it reaches the bottom.’

Henri Matisse famously recommended the amputation of tongues to anyone serious about painting, no doubt, to remind them that paint is the only medium they should be concerned with. Perhaps he also thought it might save the world from nonsense although it didn’t stop him having his say. It is, though, a salutary warning. The fear of blundering down alleyways of ill-judged pronouncements and sententious observation is enough to make anyone run from the keyboard.

David Hockney named his autobiography ‘That’s The Way I See It’ and I think this is the way for an artist to approach the subject. I am, most definitely, not an art historian and the more I write, the more conscious I am of the gaping holes in my knowledge, the exhibitions I haven’t seen, the galleries I haven’t visited yet. When Lucian Freud was given a personal viewing of the Titian exhibition (Titian being the painter he valued above all others) I remember he pointed out that he ‘doesn’t get out much’ and this is a problem for artists who dedicate almost all their time, walled up in the studio, grappling with their work. I think Freud worked more or less every day of his life until he didn’t feel like it one day and died. However, writing from an entirely personal and subjective viewpoint does make you free to wander among all the influences that have shaped your own work without pretending to be an authority and this is a highly enjoyable exercise. And, of course, a good get out clause.

Artists

In spite of all the revolutions of modernism and beyond that have enriched our means of expression through art, I still prefer to think in terms of individual artists. Distinctions between art movements seem less important than the way each artist has gone about expressing their intention in paint or whatever medium it is they have chosen to exploit. After all, it’s writers, critics, journalists etc who ascribe patterns and movements to the work. No Impressionist thought of him or herself as an ‘Impressionist’. Braque and Picasso didn’t call themselves ‘Cubists’. They were painters. No doubt, the cave painters of Lascaux were grappling with the problems of representing their thoughts in much the same way as later artists. Picasso seemed to think so.

I’m not trying to suggest that art movements don’t exist or that painters are not embedded in the current wave of whatever is happening. In any case, it’s artists who instigate movements in art. But rather that artists have always been adventurers and explorers pursuing an individual way of seeing whether it’s El Greco or Van Gogh or Freud and it’s this personal pursuit, often in obscurity and isolation, that unlocks the doors.

El Greco, in particular, seems to be an artist who is difficult to pin down to a particular era. Van Gogh, one of the most influential artists in history, worked away completely disregarded. And Lucien Freud was informed by the critic, Kenneth Clarke, that, in changing to a painterly style, he was throwing away all that was remarkable in his work. Thank God, he took no notice.

Ages, movements, fashion, seem of less interest and relevance than individuals and how they have personally reinvented the world through visual art. For me, it’s fascinating to think about how other painters have lived and worked and solved problems and exploited paint or marble or whatever. It is, after all, a working life, more often than not beset with difficulty and insecurity, but driven by a personal view and a compulsion to create something out of raw materials.

Portraits

If you can stand the horribly precarious nature of the profession, painting is a wonderful thing. You can be master or mistress of all you survey since only you can set the rules. Quite a privilege in life, really.

But it’s not quite so straightforward when it comes to portraits, or, at least, commissioned portraits. The clients may reasonably wish to have some input into the decisions to be made about the portrait and would, perhaps, like some idea of when the finished work will be delivered having agreed to part with all that money. A certain leap of faith is required. As the painter you have to do your own thing but, hopefully, without offending anyone so the process can be a bit of a high-stakes business for all concerned although if you have a Holbein or a Van Dyke on hand the risks are seriously diminished. However, even a painter as brilliant as John Singer Sargent had to accept defeat on occasion, once admitting that he had to avoid meeting a certain lady in the street after a humiliating failure with her portrait.

Court painters like Van Dyke or Velasquez were, naturally, faced with special challenges with regard to their patrons’ wishes although the Spaniard seems to have made the fewest concessions.

Imagine being Hans Holbein and required to present Henry VIII, one of the most powerful and unpredictable tyrants in Europe, with portraits of prospective brides. Christina of Denmark granted him a three hour session. No pressure. Holbein knew how good he was and probably relished the challenge. His portrait of sixteen year old Christina is one of the loveliest in the National Portrait Gallery in London, full of warmth and character.

She turned Henry down, anyway, remarking, ‘If I had two heads I would happily put one at the disposal of the King of England.’

Even worse, imagine being Anthony Van Dyke and having to elevate the absurd Charles I to god-like status. Even in the hands of a genius like him it’s hard to keep a straight face.

Give me his wonderful portrait of the ninety-two year old painter, Sofonisba Anguissola, anytime.

But even if you are not having to satisfy the whims of powerful patrons, the pressures involved in producing a commissioned portrait can still be intense. Pretty much everyone involved is taking a risk. I tend to be so obsessed with the work from my own point of view that I can sometimes forget that it’s a nerve wracking experience for the subject to finally arrive at the studio to view the finished effort and the person commissioning the work is probably worrying about the possible loss of several thousand pounds with the offending canvas hidden away in the garage. Commissioning a portrait is, on the whole, not something anyone goes into lightly. The whole process can take months from beginning to end so quite a lot is at stake when the time comes to hand over the finished painting.

For my part, I can only give each and every project the utmost care. Not being one of the aforementioned geniuses, I put my faith in time and limitless application to arrive, eventually, at a finished painting.

Photography

I’m no professional photographer, which is probably a good thing, but I’ve always had a love affair with these beautiful, design objects that sit so nicely in the hand and perform miracles with light. I remember standing as a boy on a North London pavement gazing longingly into a camera shop window. A man standing next to me leaned down and said, “No harm in looking, eh?”.

Not many people can be like Lucien Freud and demand months or even years of sittings from subjects. In fact, one of the things I admire most about him was his bloody-minded, uncompromising attitude to the time a painting might take. Out of necessity, other means have to be employed.

The use of photographs in portraiture has traditionally been contentious with good reason. For me, it’s an intrinsic and essential part of the work but it’s only a starting point. The painting is everything and there is really little difference in the way I go about the painting than from using a live model. The important thing is to use each available tool in the most constructive way. There is absolutely no way that I can ask busy clients to come to my studio, half a mile down a muddy track in remote rural Norfolk, England, and sit for days and weeks with no knowledge of when the torture will end. Therefore, it stands in for the real thing but only insofar as it gives me a basic model and a gallery of the hundreds of subtle expressions that make up the personality of the subject. The real thing, the thing that I am painting, is the impression and the memory of the person I have got to know through our meetings and this is far more real than the photographs.

In fact, the painting and the photograph are worlds apart in the sense that the photograph is only 100th of a second whereas the painting develops over an extended time and the many layers and stages of work are built into the end result and, since it’s manual work, the end result is a unique artefact. However, I must hurry to say that I’m only talking in the context of my own work. The ‘hand of the artist’ business has long been deconstructed and serious photographers would be aghast at the idea that their work was not the result of long consideration and a unique eye. But, as far as I’m concerned, the camera is only a tool and any tool that helps you get to where you want to be is to be seized upon. Of course, there’s a big trade-off. You don’t have the living and breathing person with you and, crucially, three dimensions which is a world away from the two dimensions of a photograph. This has to be rediscovered through the painting. But you do gain time which is something I need a lot of.

Method

I must admit that I am not very much preoccupied by process. The only thing that really matters is the end product and how it’s arrived at seems to me less important. That’s not to say I wouldn’t like to be a fly on the wall in the studio of Frans Hals or Joaquín Sorolla and watch them work through a portrait.

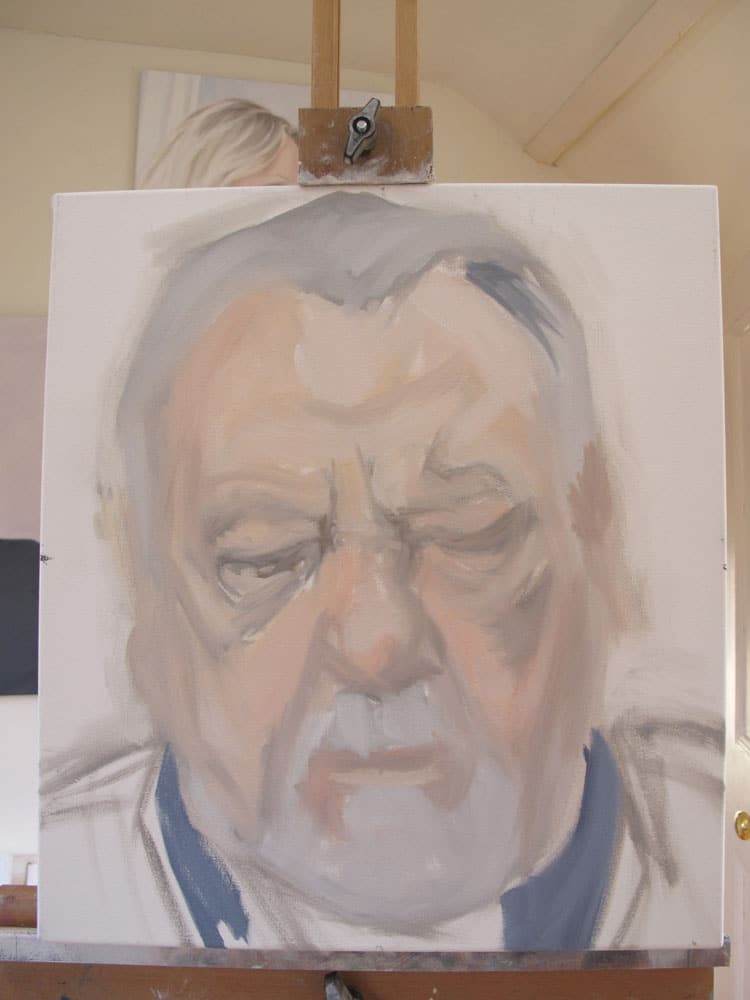

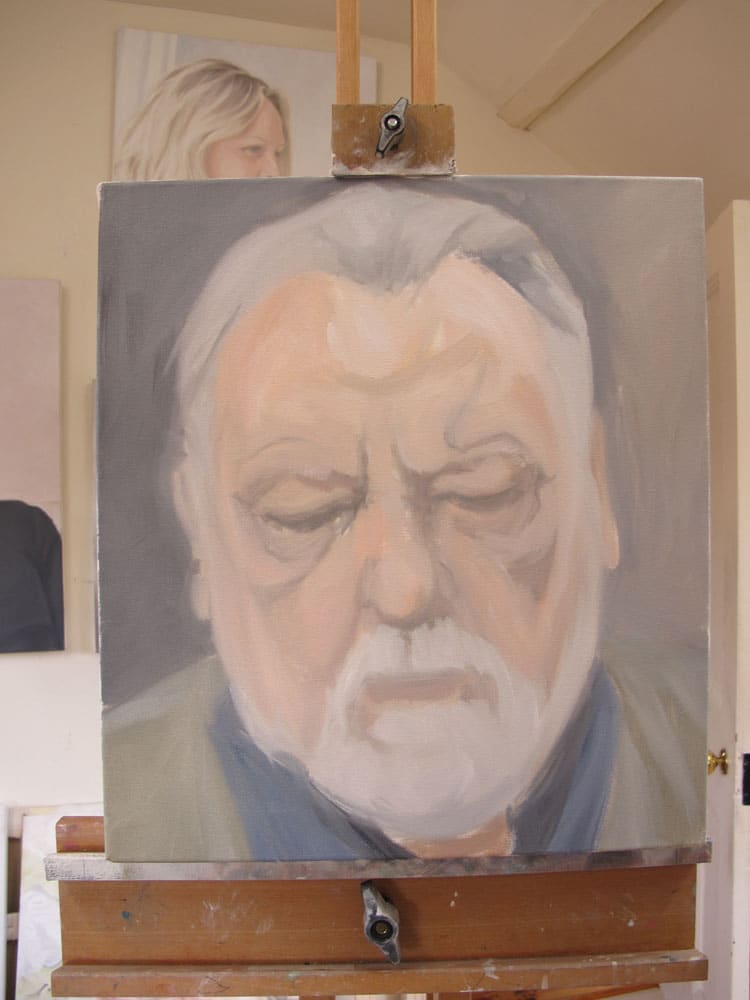

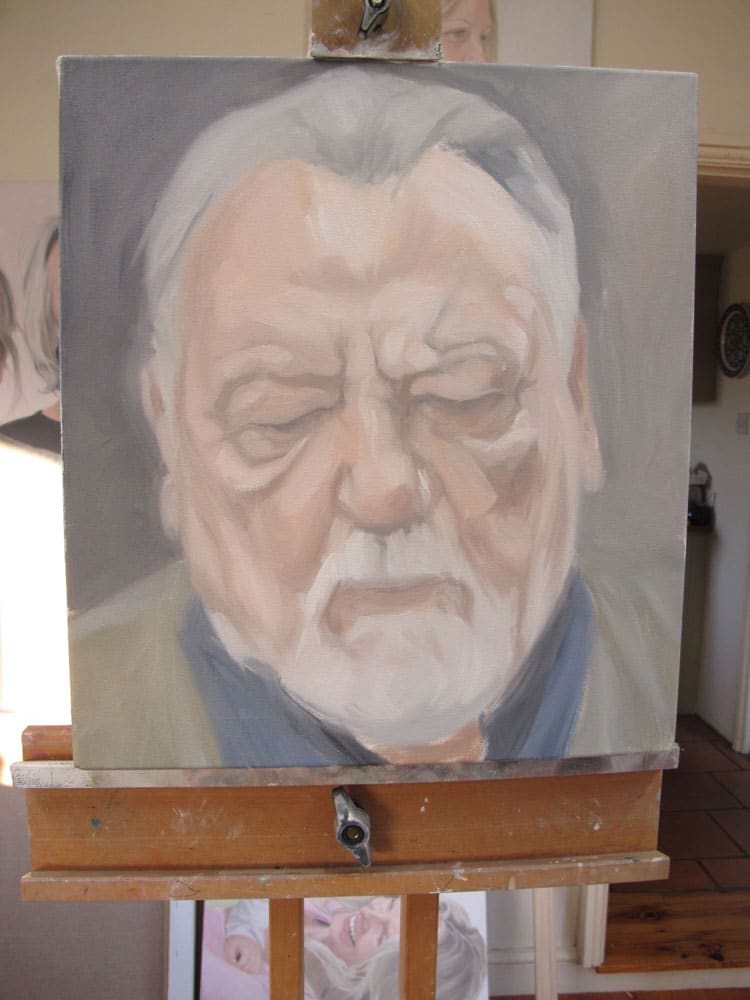

I’m an impatient painter and I do everything I can to get as quickly as possible into the nitty gritty. I start very quickly and broadly and then everything gradually slows down as I get ever deeper into the work so, for me, it’s essential not to waste time at the beginning. Things are only going to get more demanding as I go along so the best way is to go at it with a loaded brush right at the start. After all, a brush is a sensitive and flexible tool, oil paint can be easily wiped off and you are always drawing and modelling with the paint as you go along. I find it also avoids the temptation to get bogged down in detail in the early stages and it helps to capture the subject from the word go and this can be carried forward into all the following stages. After all, the charcoal drawing is lost in the painting and the whole process is often one of constantly losing and then recapturing the portrait. At any rate, it works for me, and that’s really all that matters.

There is a photograph of Sorolla making the charcoal drawing for his lovely portrait of his wife, Clotilde in a Black Dress. It’s a masterly piece of work and seems to lay down everything that he has in mind for the painting so one method is, of course, no better than another.

Lucien Freud’s method worked for him but it was highly unusual. Beginning with the head, he would work his way, inch by inch, across the canvas more or less finishing each section as he went rather like a jigsaw puzzle.

Nonetheless, each painting is of immense power, perfectly integrated and harmonised across the entire canvas.

I’m not very much concerned with the paraphernalia of the oil painting craft. I like the matt surface of my paintings which comes from using a minimum of medium containing no exotic mixtures. I like to paint ‘wet in wet’ so that the paint is always malleable. My colour palette is very limited and I’ve found that for portraiture it works very well. The canvases are all oil primed linen and the paints and brushes are of the best quality I can find.

In truth, the work itself is so demanding and difficult and I’m so impatient to get on with the job that I resent any time spent on experimentation with materials. It’s probably my own peculiar neurosis but the wingèd chariot is forever hurrying near and there is so much to be done.

My paintings are not at all thick in terms of the amount of paint used but there are, in fact, many layers of work involved with much correcting and over painting and it is often not until the last few sessions that things will come together. Basically, I feel my way along through a painting. I do know what I’m doing, where I’m going and what I want to achieve, but it’s not something that I could ever put into words.

I once gave an interview to an MA student about my work. She was looking around at the paintings in the studio and remarked, ‘It all looks so effortless’. I could have laughed. I could have cried. I was, at any rate, gratified that the paintings appeared to be unforced but the effort required to get them to look like that had nearly killed me. One thing that is vitally important for me is to keep everything in a fluid state at all times and that includes the thinking part of the work. An open mind and open senses are the only reliable guides.

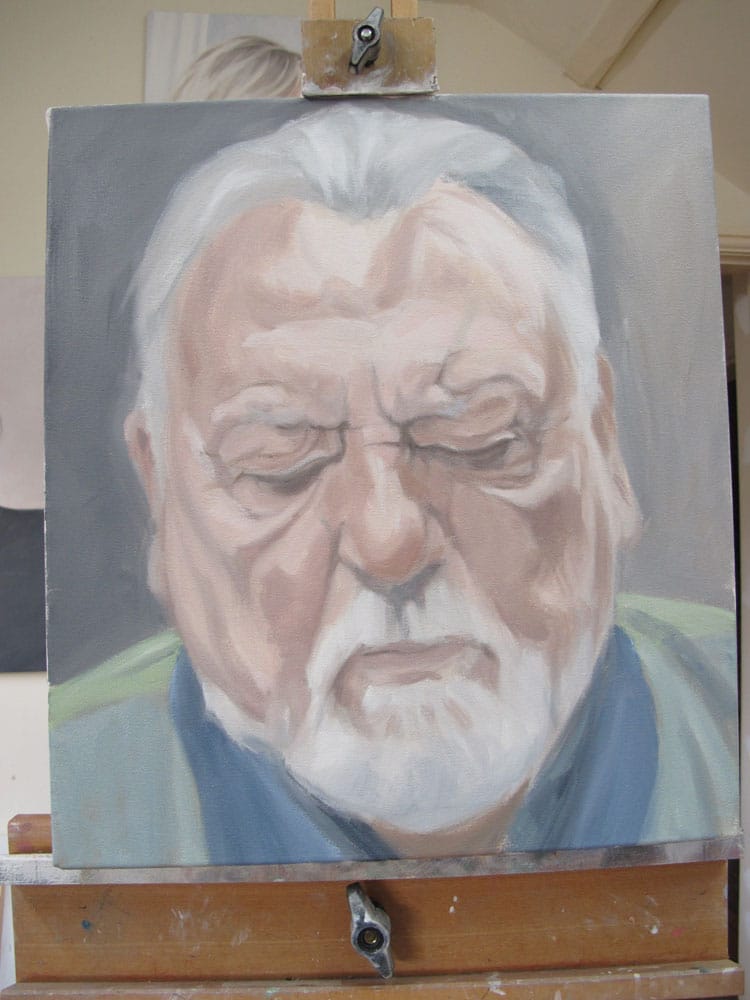

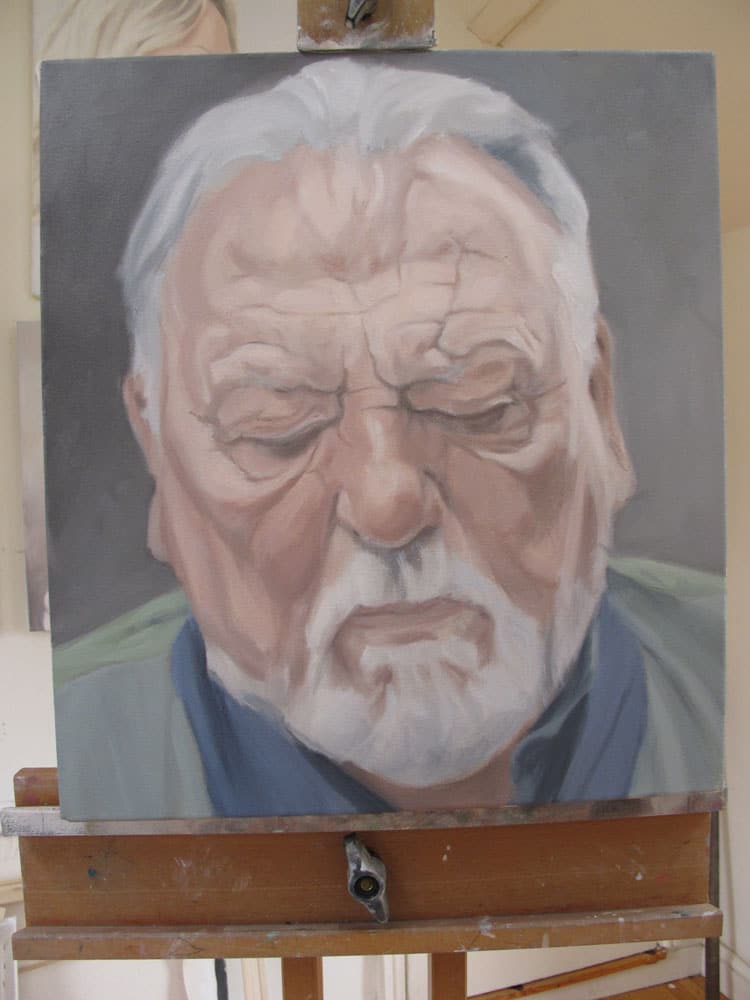

This is the sequence of work from beginning to end for my portrait of the actor, Kenneth Cranham.

The Statement

Despite a reluctance to find words to illustrate the paintings, I have to concede that it’s necessary to give some account of what you are up to as an artist and all the background information available in exhibitions definitely enhances our experience. Undoubtedly, some grounding in genres such as conceptualism, abstraction, minimalism etc. increases the appreciation of the work just as it would, for instance, with the music of Stockhausen.

However, I hardly think my own work is so obscure as to need much theoretical underpinning but I did, eventually, come up with these words:

‘My work is about understanding and revealing the character and the personality of the people I paint in a way that I hope they will recognise as a truthful reflexion of themselves.

Each one of us is a complex individual with a rich history written in our features and our thoughts and emotions reveal themselves continually in our expressions. The challenge for me is to discover as much as I can of the essence of each person and bring this to life in the painting.

It is, actually, quite a privilege to study another person so intimately and the difficult task of pulling off something that you hope will work, not just for you but for them and the other people involved, is a responsibility that requires an infinite amount of time and care on my part.’

Very illuminating to hear an artist speak about their work, and how they view other artists’ who have influenced. It’s never easy to put, what is a visual language, into words, but I enjoyed this insight. Thank you.

Delicious

I remember reading in the 1960’s an essay on art by American philosopher, Suzanne Langer, in which she observed that art sprang from that sphere of the human psyche ‘inaccessible to words’. Even so, it does not mean we should not use those words at our command to get a bit closer to that ‘inaccessible’ zone. Most such investigations are voiced by art historians or critics, so it’s very refreshing to read the observations by a practicing artist, especially touching on personal methodology and techniques – often be a mystery to the general public. Of particular interest are the illustrations of the various stages of the approach to the portrait of famous actor, Kenneth Cranham, ending with the acutely observed final product. A real triumph.

Always inspirational to read a great artist explain their own personal process in creating; and to put that in the context of other artists.

There is so much to unpack here and to chew on.

Thanks so much for all this illumination.

I’ve just re-read this piece. It feels like a conversation that flows through ideas and experiences and reading it, I was born along in its thoughtful and thought-engendering stream – a lovely and enlightening read, thanks Terry.