Portrait painting is an interestingly democratic business. The status or the self-image of the person you are painting is of far less importance than what you discover of them through observation. Of course, you have to treat people with respect and try to understand the way they may feel about themselves but the process of studying someone so intensely does means that each subject becomes just one fascinating and unique individual among many.

The landscape of the human face must be the richest anywhere on earth and the business of discovering a person’s character and personality through a study of their features and habits can often seem like a journey of exploration and excavation, knowing that there is gold to be discovered there so long as you dig deep enough.

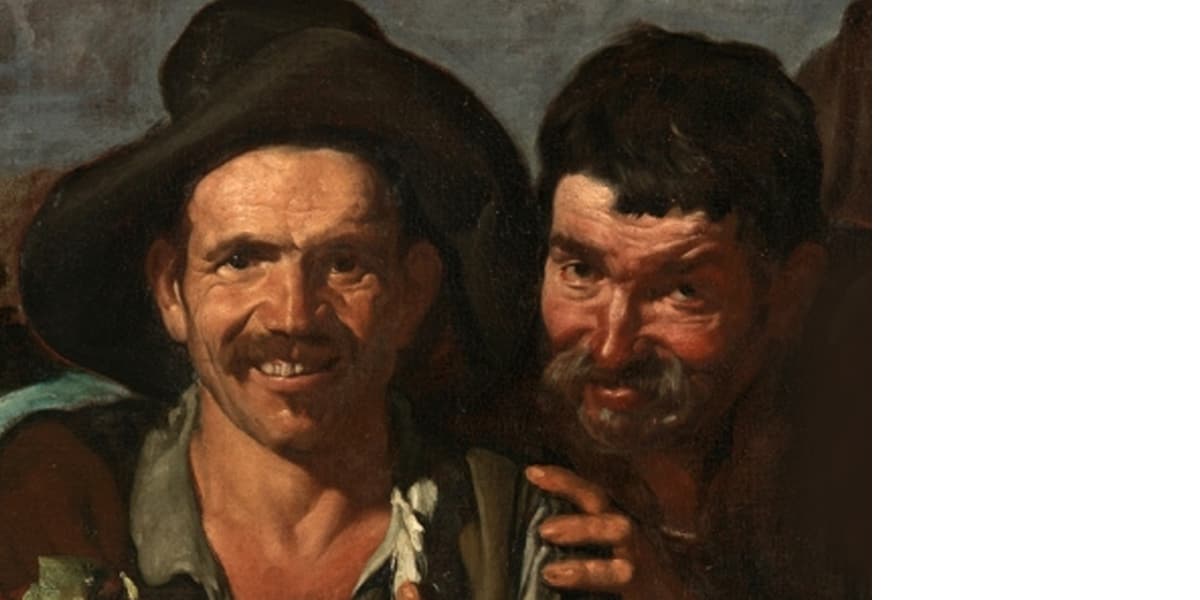

Velásquez

Velásquez’s two characters, above, from The Feast of Bacchus are a demonstration of how intensely he applied himself to the study of the people of Spain. There is an inscription somewhere that reads ‘He painted us as we are’ but I can’t, for the life of me, remember where I saw it. Maybe I imagined it but I thought it was on his statue in Seville and, even if I did imagine it, I think it’s appropriate. At any rate, it was a feature of Velasquez’s approach to his work that he gave the peasantry the same care and dignity that he gave his employer, Phillip IV of Spain.

The Feast of Bacchus (detail)

The wonderful portrait of his North African assistant and slave, Juan de Pareja, is an example.

While in Rome, Velásquez was honoured with membership of the Congregazione dei Virtuosi and for their annual exhibition he chose to show this painting. It must have been a bit of a jolt for the members to see someone from the lowest ranks of society presented with so much presence and authority.

The point is that Velásquez did nothing to impose this on his subject. He merely presented Pareja with the dignity and natural nobility that he saw in the man. It’s very moving.

He later freed Pareja who went on to become an independent painter in his own right.

The court of Philip IV included dwarfs, who were kept as playmates of the Royal children and they, also, became subjects for Velásquez and, again, each man is treated with the same even-handed respect as every other member of the household.

They are, Don Diego de Acedo, Sebastián de Morra, Francesco Lezcano and Don Juan Calabalaz.

Probably the most famous of Velasquez’s portraits of the people is The Water-Seller of Seville.

It’s not hard to see why this man’s profile appealed so much. How much more exciting than the inbred features of Phillip IV, entrapped in his Royal status, forever conscious of his divine right. How much more genuinely noble this street seller is.

The Water-Seller of Seville

The Water-Seller of Seville

The Water-seller of Seville (detail)

Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Mary and Martha

Many of Velásquez’s paintings are illustrations of New Testament stories. Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Mary and Martha is one such. The painting shows a servant girl pounding garlic with an old woman making a point to her, or, perhaps, drawing her attention to the room in the background where Christ is preaching to Mary and Martha. Apparently, Martha has come from the kitchen moaning about being left to do all the work while Mary sits and chats with Jesus. A common enough complaint. However, Jesus admonishes her, saying that Mary’s attention to his teachings is the greater work.

It seems quite an ambiguous scene but the debate about the temporal ‘good works’ life and the spiritual contemplative life was certainly important at the time and maybe the old woman is delivering a lecture of some kind to the servant girl. Interestingly, Mary, Martha and Christ are painted in a fairly cursory fashion compared to the rest of the work.

But, frankly, I couldn’t care less about the biblical story. For me, this is a wonderful, stand-alone portrait of a young woman that demonstrates Velásquez’s unrivalled mastery of painting.

Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (detail)

Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (detail)

Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (detail)

Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Mary and Martha

Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (detail)

Along with the glistening, wet fish and the other items that make up the still life on the kitchen table, I wouldn’t mind betting that Velásquez was also a lot more preoccupied with this girl than with the niceties of theological debate.

Kitchen Scene with Christ at Emmaus

Kitchen Scene with Christ at Emmaus is a similar situation featuring another beautifully painted woman.

Again, the figures who are the subjects of the story are briefly delineated in the background, but the serving girl, arrested in a moment of abstraction or, perhaps, listening to the conversation behind, is utter perfection.

In the foreground Velásquez gives us another fabulous still life.

Kitchen Scene with Christ at Emmaus (detail)

Kitchen Scene with Christ at Emmaus (detail)

Kitchen Scene with Christ at Emmaus (detail)

Caravaggio, Gentileschi

Madonna of Loreto

If you put a euro in the slot to light up Caravaggio’s Madonna of Loreto in Sant’Agostino’s in Rome, revealed to you is a ravishing young woman who dispels in a moment any interest you might have had in The Virgin Mary.

This insouciant beauty leans in a doorway, somewhere in a less upmarket district of Rome, casually gracing the visiting peasants with her presence, the toes of one divine bare foot resting perfectly on the stone step.

It is a stunning portrait of a beautiful woman.

The two barefoot peasants have obviously trekked miles with their walking staffs but their faces are alight with the fulfillment of promise. The certainty of religious fervour shines forth. Never mind that they probably haven’t got a bed for the night, it’s been worth it for this ecstatic moment of blessing.

Of course, as it’s Caravaggio, it’s loaded with sensuality. The delight he took in painting the Madonna’s divine neck can be readily imagined. She may be representing the passive receptacle of some ineffable mystery, but she is also a model of human physical perfection that anyone would drag themselves through the streets to meet.

Caravaggio’s breathtaking innovations in the use of light must have seemed sent from heaven by the orchestrators of The Counter Reformation, although I think they struggled to cope with his equally breathtaking realism and his use of live models for his work rather than the normal constructs that were meant to represent the divine.

Caravaggio, Gentileschi

If you put a euro in the slot to light up Caravaggio’s Madonna of Loreto in Sant’Agostino’s in Rome, revealed to you is a ravishing young woman who dispels in a moment any interest you might have had in The Virgin Mary.

This insouciant beauty leans in a doorway, somewhere in a less upmarket district of Rome, casually gracing the visiting peasants with her presence, the toes of one divine bare foot resting perfectly on the stone step.

It is a stunning portrait of a beautiful woman.

The two barefoot peasants have obviously trekked miles with their walking staffs but their faces are alight with the fulfilment of promise. The certainty of religious fervour shines forth. Never mind that they probably haven’t got a bed for the night, it’s been worth it for this ecstatic moment of blessing.

Of course, as it’s Caravaggio, it’s loaded with sensuality. The delight he took in painting the Madonna’s divine neck can be readily imagined. She may be representing the passive receptacle of some ineffable mystery, but she is also a model of human physical perfection that anyone would drag themselves through the streets to meet.

Caravaggio’s breathtaking innovations in the use of light must have seemed sent from heaven by the orchestrators of The Counter Reformation, although I think they struggled to cope with his equally breath-taking realism and his use of live models for his work rather than the normal constructs that were meant to represent the divine.

His Salome with the Head of John the Baptist features a fascinating portrait of the butcher who is placing the head on the tray as if she has just ordered a pound of beef. His left-hand rests with familiar professionalism on the hilt of his sword, suggesting that he spends all day chopping off heads.

You feel you might encounter this rough individual in a backstreet macelleria in Naples.

Rather than the biblical scenes which are the subjects of the paintings, I would suggest that Caravaggio’s overriding fascination is with his models and their very human characteristics.

Mary Magdelene as Melancholy

Similarly, this by Artemisia Gentiselchi, a painter much influenced by Caravaggio. The fact that she is Mary Magdalene as Melancholy seems incidental to this amazing study of a woman in the heavy grip of depression. She looks blankly out through eyes devoid of emotion or motivation. The blood has gathered in her hand from inertia and a slight patina of moisture seems to glisten around her features like someone in a deep slumber. And she is well beyond caring how much flesh is on display.

Mary Magdlene as Melancholy (detail)

Mary Magdalene as Melancholy (detail)

It seems that, for painters like these, the driving force is not a representation of the divine but an intimate study of humanity, and the biblical or allegorical themes are an opportunity to apply their phenomenal powers as painters to showing us who we are, as we are.

Spaniards

I don’t know what it is about Spanish painters but they seem to have some kind of a hotline to the human condition. The intensity with which they connect to what it is to be human and to their Spanish identity seems to be part of the fundamental genetic make-up. If my earlier quote regarding Velásquez isn’t a figment of my imagination, I think it’s significant that it reads, ‘He painted us…’ and not, ‘He painted the people…’

There’s another quote that I’ve read but, unfortunately, can’t place which says, (paraphrasing heavily), ‘Some lands are verdant and fertile but God gave us a country that we have to wrestle like a lion’. Maybe this elemental sense of struggle has something to do with the urgency with which they confront life and depict life.

Goya

Goya was another painter of genius and a man of great humanity who was deeply connected with his fellow people and made a lifelong record of Spanish life. Much of his work addressed the lives of peasants, often within the context of the extreme events taking place around them.

His beautifully intimate and contemplative self-portrait from 1815 leaves me with a sense of knowing the man like an old friend.

Sorolla

There can be few painters more deeply immersed in their culture than Joaquín Sorolla who made an almost encyclopaedic body of work depicting the people of Spain including the vast mural for New York’s Hispanic Society of America in 1913, Vision of Spain. Below is just part of this monumental work.

Vision of Spain

This painting, Joaquina The Gypsy by Sorolla, is one of the most moving portraits I can think of.

It is just a painting of a woman contentedly holding her child and yet it gives us an experience of her and, by reflexion, ourselves, that is simply beyond words.

Some painters, some paintings, have the ability to seemingly remove an unseen barrier and bring us into contact with the lives of others.

The Portrait of a Seated Woman Holding a Fan (detail) by the irrepressively benign Frans Hals arrests us with a little jolt of recognition, as if we would say, ‘We know each other, don’t we?’

Van Gogh’s Portrait of a Woman with her Hair Loose, one of my all time favourite portraits, is a deep and compassionate painting of a young woman seemingly caught in a sensitive, vulnerable moment of thought.

It’s as if these paintings have created an infinite moment of time that can be relived over and over again.

I sometimes get a bit carried away with the idea that paintings like these might help us to a better understanding of ourselves showing us, perhaps, that we are of the same stuff with the same concerns and the same needs whoever we may be. The affliction is particularly acute when it comes to portraits since that’s my particular area of work at the moment.

Expecting paintings to intervene and lead us, hand in hand, across the sunlit uplands of harmony and fellowship is, maybe, going a little far, but I think it remains true that we are incomplete without the arts. Indeed, we are less than human without them. And it could well, also, be true that the understanding and appreciation of our common humanity will be of far more use to us in the future than the manipulation of technology.

Rembrandt

From Archway in North London you can take the 210 bus up through Highgate Village and out along the leafy charm of Hampstead Lane. The bus puts you down alongside wooden fencing overhung by large sycamores where, to the right, considerable wealth is stacked up in private, gated avenues. A little further on, to the left, you descend a curving path between shrubberies to reach Kenwood House, standing like a mighty ship overlooking London, spread out to the South. It’s a truly impressive piece of architecture in a stunning location. Walking along the gleaming, white South side of the building put me in mind of the Arena Sferisterio at Macerata in Italy’s Le Marche, a vast open-air opera stage where the audience is as much on show as the actors and a procession can take a good twenty minutes to get from one side of the stage to the other.

But never mind all that. Once inside, you pass through the lovely rooms until you arrive at the business end of the art collection. Frans Hals’ brilliant portrait of Pieter Van Den Broecke is to the left, annoyingly hung between two bright windows. One of Vermeer’s women is plucking her guitar a little further on. But if you do a 180º turn, you are confonted with this:

However familiar you may be with this masterpiece, the effect of standing in front of it while Rembrandt’s black eyes look right through you is still extraordinary.

Not only do you feel the full weight of his dispassionate gaze upon you, he also gives you the complete, unsentimental assessment of his own self with the battle scars of life and work, success and disappointment for all to see.

I believe the legendary art historian, Erwin Panofsky, said something to the effect that great portraits tell us, not only about the subject, but also about what they share in common with everyone else and there can’t be another painting that so forcefully insists that you recognise this truth.

Whether or not we can be totally comfortable with the conclusion Rembrandt seems to have reached about himself and us is another matter. Fortunately, Frans Hals is close at hand.

Great Terry!

Enjoyed reading , will continue tomorrow for sure! Yes, you’re absolutely right about Spanish painters, their earthy power and interest of the human condition at all levels is magnificent. They enter into the soul of the subject.

Did you know, that when Goya escaped to Bordeaux, he abandoned his house and paintings in Madrid- and the most sinister thing is his head is missing! Somebody defiled his tomb and decapitated him!!

Someday we’ll have a good chat! Love to Mandy! Lydia

Thank you, Lydia! Love to you both.